reading

Losing the ability to read

07/07/10 11:14

For those

of you who have access to the New Yorker, there is a

great article by Oliver Sacks on people who have lost

the ability to read after a stroke. They can still

write, but they cannot go back and read their own

writing. I wish the entire piece was available

online, but there is an abstract, and hopefully if

you are interested, you can chase it down at the

library. It's subscription only for the full article.

(So really, subscribe to the New Yorker, what else

can I say? So many good articles in it.) But back to

this one: It's fascinating, as is much of what Oliver

Sacks writes:

Whatever language a person is reading, the same area of inferotemporal cortex, the visual word form area, is activated. Why should all human beings have this built-in facility for reading when writing is a relatively recent cultural invention? ... Writing, a cultural tool, has evolved to make use of the inferotemporal neurons’ preference for certain shapes. The origin of writing and reading cannot be understood as a direct evolutionary adaptation. It is dependent on the plasticity of the brain, and on the fact that experience is as powerful an agent of change as natural selection. We are literate not by virtue of a divine intervention but through a cultural invention and a cultural selection that make a creative new use of a preëxisting neural proclivity.

Harold Engel, the patient who presented himself to Sacks after losing his ability to read, had been a novelist, and wrote mysteries. The story of how he worked to start writing again, without being able to edit or revise his drafts directly, is amazing - dictation and audio recordings and having someone read his drafts to him had to take the place of him being able to reread what he had written.

Read more: http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/06/28/100628fa_fact_sacks#i...

Whatever language a person is reading, the same area of inferotemporal cortex, the visual word form area, is activated. Why should all human beings have this built-in facility for reading when writing is a relatively recent cultural invention? ... Writing, a cultural tool, has evolved to make use of the inferotemporal neurons’ preference for certain shapes. The origin of writing and reading cannot be understood as a direct evolutionary adaptation. It is dependent on the plasticity of the brain, and on the fact that experience is as powerful an agent of change as natural selection. We are literate not by virtue of a divine intervention but through a cultural invention and a cultural selection that make a creative new use of a preëxisting neural proclivity.

Harold Engel, the patient who presented himself to Sacks after losing his ability to read, had been a novelist, and wrote mysteries. The story of how he worked to start writing again, without being able to edit or revise his drafts directly, is amazing - dictation and audio recordings and having someone read his drafts to him had to take the place of him being able to reread what he had written.

Read more: http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/06/28/100628fa_fact_sacks#i...

The web shatters your focus

06/04/10 10:54

Navigating

linked documents, it turned out, entails a lot of

mental calisthenics—evaluating hyperlinks, deciding

whether to click, adjusting to different formats—that

are extraneous to the process of reading. Because it

disrupts concentration, such activity weakens

comprehension. A 1989 study showed that readers

tended just to click around aimlessly when reading

something that included hypertext links to other

selected pieces of information. A 1990 experiment

revealed that some “could not remember what they had

and had not read.”

Even though the World Wide Web has made hypertext ubiquitous and presumably less startling and unfamiliar, the cognitive problems remain. Research continues to show that people who read linear text comprehend more, remember more, and learn more than those who read text peppered with links. In a 2001 study, two scholars in Canada asked 70 people to read “The Demon Lover,” a short story by Elizabeth Bowen. One group read it in a traditional linear-text format; they’d read a passage and click the word next to move ahead. A second group read a version in which they had to click on highlighted words in the text to move ahead. It took the hypertext readers longer to read the document, and they were seven times more likely to say they found it confusing. Another researcher, Erping Zhu, had people read a passage of digital prose but varied the number of links appearing in it. She then gave the readers a multiple-choice quiz and had them write a summary of what they had read. She found that comprehension declined as the number of links increased—whether or not people clicked on them. After all, whenever a link appears, your brain has to at least make the choice not to click, which is itself distracting.

There's lots more, and it is astonishing, at Wired....

Even though the World Wide Web has made hypertext ubiquitous and presumably less startling and unfamiliar, the cognitive problems remain. Research continues to show that people who read linear text comprehend more, remember more, and learn more than those who read text peppered with links. In a 2001 study, two scholars in Canada asked 70 people to read “The Demon Lover,” a short story by Elizabeth Bowen. One group read it in a traditional linear-text format; they’d read a passage and click the word next to move ahead. A second group read a version in which they had to click on highlighted words in the text to move ahead. It took the hypertext readers longer to read the document, and they were seven times more likely to say they found it confusing. Another researcher, Erping Zhu, had people read a passage of digital prose but varied the number of links appearing in it. She then gave the readers a multiple-choice quiz and had them write a summary of what they had read. She found that comprehension declined as the number of links increased—whether or not people clicked on them. After all, whenever a link appears, your brain has to at least make the choice not to click, which is itself distracting.

There's lots more, and it is astonishing, at Wired....

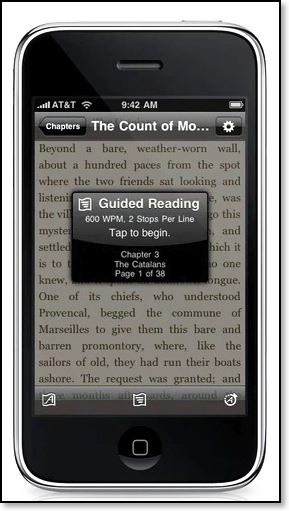

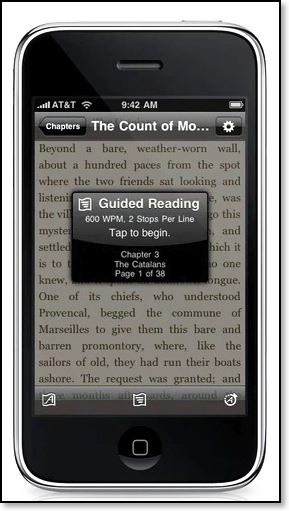

Speed reading - training or going touchfree

05/22/10 10:40

This looks

like a fun application. Find out how fast you read,

have it turn the pages for you, and improve your

reading speed all in one. QuickReader.net

Moby Dick every week

04/28/10 10:29

Hugh McGuire says:

Roger Bohn of UC San Diego, estimates that the average American consumes about 36,000 words of text per day, during leisure hours. That number includes print, email, the web, and text messaging. That’s a lot of text. At that rate the average American could read Moby Dick every week.

Roger Bohn of UC San Diego, estimates that the average American consumes about 36,000 words of text per day, during leisure hours. That number includes print, email, the web, and text messaging. That’s a lot of text. At that rate the average American could read Moby Dick every week.

How much information do we take in daily?

01/15/10 10:14

From the

Good Is Good blog:

This is per DAY! No wonder my brain hurts!

According to research from the University of California at San Diego—which has been transformed into this awesome accompanying graphic illustration by the artist Rob Vargas for Fast Company—Americans consume 3.6 zettabytes (one zettabyte is one billion trillion bytes) per day. Zounds.

This is per DAY! No wonder my brain hurts!

According to research from the University of California at San Diego—which has been transformed into this awesome accompanying graphic illustration by the artist Rob Vargas for Fast Company—Americans consume 3.6 zettabytes (one zettabyte is one billion trillion bytes) per day. Zounds.

Speed reading

11/25/09 10:49

I'm not a

speed reader, although I am a very fast reader. I

have fond memories of sitting with my dad, playing

with a toy he had brought home. It was flat metal

plate with a sliding viewer in it, one that would

open and shut with a snap. He slipped lists of words

into it, and could adjust how long they displayed in

the viewer before it snapped shut. His playful toy

increased my reading speed, and as it increased, the

word lists grew into phrase lists, longer and longer,

all to be recognized in a fleeting view that he could

make shorter and shorter. It certainly worked!

I've never felt the need to take a speed reading course, but if you do, here's some hints from someone who has ramped up their reading rate in a different way.

In this article, I’m going to share the lessons I learned that doubled my reading rate, allowed me to consume over 70 books in a year and made me a smarter reader. I’m also going to destroy some speed-reading myths, to show you it isn’t magic but a skill anyone can learn.

My first introduction to the concept of speed reading was from a book, Breakthrough Rapid Reading. I’ve since moved away from a few of the concepts taught in the book, but the core ideas were transformative. In only a few weeks, my average reading speed went from roughly 450 words per minute, to over 900.

More than just words per minute, speed reading helped instill a new passion for reading. Because I gained more control over my reading abilities, my desire to read went up. That new motivation made me a voracious reader, in one two year period, I had read over 150 books.

Here are a few of the lessons I’ve learned from several years of speed reading: Continue reading at 7 keys...

I've never felt the need to take a speed reading course, but if you do, here's some hints from someone who has ramped up their reading rate in a different way.

In this article, I’m going to share the lessons I learned that doubled my reading rate, allowed me to consume over 70 books in a year and made me a smarter reader. I’m also going to destroy some speed-reading myths, to show you it isn’t magic but a skill anyone can learn.

My first introduction to the concept of speed reading was from a book, Breakthrough Rapid Reading. I’ve since moved away from a few of the concepts taught in the book, but the core ideas were transformative. In only a few weeks, my average reading speed went from roughly 450 words per minute, to over 900.

More than just words per minute, speed reading helped instill a new passion for reading. Because I gained more control over my reading abilities, my desire to read went up. That new motivation made me a voracious reader, in one two year period, I had read over 150 books.

Here are a few of the lessons I’ve learned from several years of speed reading: Continue reading at 7 keys...

200 best beach reads!

07/23/09 11:28

From NPR -

they haven't winnowed this down to the 100 best yet.

These are the 200 finalists...

The Accidental Tourist by Anne Tyler

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Affinity by Sarah Waters

The Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon

Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner

Animal Dreams by Barbara Kingsolver

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

The Art of Racing in the Rain by Garth Stein

More....

I have read all but Affinity, and the Art of Racing. Angle of Repose is one of my all time favorite books.

The Accidental Tourist by Anne Tyler

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Affinity by Sarah Waters

The Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon

Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner

Animal Dreams by Barbara Kingsolver

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

The Art of Racing in the Rain by Garth Stein

More....

I have read all but Affinity, and the Art of Racing. Angle of Repose is one of my all time favorite books.

What is technology going to do?

07/15/09 11:24

From the

Book Oven (Hugh McGuire), and

from a much longer post:

Here are some of the things that are coming, I think, from the inevitable drive of technology to order nature, and our human desire to have efficient sorting systems:

We’ll continue to cataloging everything (from books to people to places) online, and find better ways to sort all that information, using objective authority (eg authoritative incoming links, aka google juice), personal network authority (links/preferences from your chosen network) as relevance indicators.

We will map this network on the web, and increasingly apply it to physical space (starting with google maps, and becoming more customized and personalized)

Mobile technology will mean both that our access to cataloged information becomes ubiquitous, and our efforts to catalog things will be unconstrained

RFID, or something like it, will mean that this sorting of physical objects will move from its current general state (eg. tracking & finding something like “any copy of a certain book”), to specific (eg. tracking & finding something like “a particular copy of a certain book”), and will touch people too

We’ll get all the media we want, when we want it

We’ll get most of the data we want, when we want it

Our mobile devices will increasingly interact with our physical surroundings (point at an object, get info on it; buy it; sell it), and will become our bank, and keys, our thermostat, and more, as well as everything else it already is (telephone, email, library, map etc).

All data on the web will become structured, and mostly available

More data sets (eg government-owned) will arrive on the web, and more people will participate in using that data to understand the world, and make decisions, to order nature

Data about people will become structured, and mostly available [For a well-networked human in my circle, this has already happened: I can track their interests, on a daily basis (del.icio.us, google reader shared items, digg etc.), their movements (dopplr), their public thoughts (blogs, twitter), books they like (librarything, gutenberg bookshelf), things they buy, etc etc.]

Lots of money will be made (if all goes well, some of it by friends of mine) finding new and different ways to do all this, and more and more. In essence, we’ll continue to use the web (and increasingly, mobile devices) to better order nature. And we’ll become better ordered at the same time.

Looking at this very brief list of what’s going to happen, I can’t help but think: “so what?” Is any of this going to make people’s lives richer or more meaningful?

My suspicion is “no.” I say this as a digital native, if a relatively recent, adoptive native (starting in 2004). For myself, I have found that the price of the benefits of the web has been heavy: while the web has allowed me to do all sorts of things, to build things and relationships, and projects, I find the quality of my time on the web so often unsatisfying. In a comparison of value to me between a random “leisure” hour on the web and a random hour doing something else in the real world, the real world trumps the web almost every time. Yet the web still usually wins the battle for my time (this says as much about me as it does about the web, of course).

Here are some of the things that are coming, I think, from the inevitable drive of technology to order nature, and our human desire to have efficient sorting systems:

We’ll continue to cataloging everything (from books to people to places) online, and find better ways to sort all that information, using objective authority (eg authoritative incoming links, aka google juice), personal network authority (links/preferences from your chosen network) as relevance indicators.

We will map this network on the web, and increasingly apply it to physical space (starting with google maps, and becoming more customized and personalized)

Mobile technology will mean both that our access to cataloged information becomes ubiquitous, and our efforts to catalog things will be unconstrained

RFID, or something like it, will mean that this sorting of physical objects will move from its current general state (eg. tracking & finding something like “any copy of a certain book”), to specific (eg. tracking & finding something like “a particular copy of a certain book”), and will touch people too

We’ll get all the media we want, when we want it

We’ll get most of the data we want, when we want it

Our mobile devices will increasingly interact with our physical surroundings (point at an object, get info on it; buy it; sell it), and will become our bank, and keys, our thermostat, and more, as well as everything else it already is (telephone, email, library, map etc).

All data on the web will become structured, and mostly available

More data sets (eg government-owned) will arrive on the web, and more people will participate in using that data to understand the world, and make decisions, to order nature

Data about people will become structured, and mostly available [For a well-networked human in my circle, this has already happened: I can track their interests, on a daily basis (del.icio.us, google reader shared items, digg etc.), their movements (dopplr), their public thoughts (blogs, twitter), books they like (librarything, gutenberg bookshelf), things they buy, etc etc.]

Lots of money will be made (if all goes well, some of it by friends of mine) finding new and different ways to do all this, and more and more. In essence, we’ll continue to use the web (and increasingly, mobile devices) to better order nature. And we’ll become better ordered at the same time.

Looking at this very brief list of what’s going to happen, I can’t help but think: “so what?” Is any of this going to make people’s lives richer or more meaningful?

My suspicion is “no.” I say this as a digital native, if a relatively recent, adoptive native (starting in 2004). For myself, I have found that the price of the benefits of the web has been heavy: while the web has allowed me to do all sorts of things, to build things and relationships, and projects, I find the quality of my time on the web so often unsatisfying. In a comparison of value to me between a random “leisure” hour on the web and a random hour doing something else in the real world, the real world trumps the web almost every time. Yet the web still usually wins the battle for my time (this says as much about me as it does about the web, of course).

Bookseer

07/05/09 11:20

Enter what

you have just read and liked, and the bookseer will offer up some

suggestions. I'm not sure how great they are, but

it's fun!

How students learn now

06/20/09 10:56

and what it means for technical documentation.

This piece includes a powerful movie put together by students, talking about their own learning styles in the age of tech. Worth a read, and worth a viewing!

Some statistics on eBooks

06/04/09 10:35

From Alan

Watt at

Wattpad: (and

note, these statistics cover the Wattpad reader

application only)

Our first report covers both country and handset/manufacturer data with some fun facts attached to the end of the report. We expect to expand the report to include more axes of information in the coming months.

Here is the highlight:

• In terms of usage, Indonesia is the top country (39%), followed by US (28%) and Vietnam (9%).

• Java devices are still the most used mobile platform for reading e-books. 63% of e-book usage come from Java devices while iPhone usage grows to 33%.

• Nokia dominates the top device list with 4 of the top 6 are Nokia Series 40. iPhone claims the top spot.

• iPhone dominates US e-book usage with 78% of iPhone usage comes from North America. Nokia still dominates the rest of the world.

• Blackberry usage grew over 400% since the launch of App World. Indicates the effectiveness of an application storefront.

As you can see, although e-reading on iPhone dominates the headlines of US media in the last few months, e-reading is truly a global phenomenon and it is more than “just the iPhone”. ...

Here are some fun facts that you might find interesting too:

• Usage typically surges on weekends by 10%

• Daily usage peaks in the evening at bed time (local times).

• Blackberry users read the least per day as shown in our average daily number of sessions. Perhaps preoccupied by the influx of emails! Blackberry users have about 1.6 session per day, while iPhone users have 2.3 and Java phone users read the most with 2.6 sessions per day.

Our first report covers both country and handset/manufacturer data with some fun facts attached to the end of the report. We expect to expand the report to include more axes of information in the coming months.

Here is the highlight:

• In terms of usage, Indonesia is the top country (39%), followed by US (28%) and Vietnam (9%).

• Java devices are still the most used mobile platform for reading e-books. 63% of e-book usage come from Java devices while iPhone usage grows to 33%.

• Nokia dominates the top device list with 4 of the top 6 are Nokia Series 40. iPhone claims the top spot.

• iPhone dominates US e-book usage with 78% of iPhone usage comes from North America. Nokia still dominates the rest of the world.

• Blackberry usage grew over 400% since the launch of App World. Indicates the effectiveness of an application storefront.

As you can see, although e-reading on iPhone dominates the headlines of US media in the last few months, e-reading is truly a global phenomenon and it is more than “just the iPhone”. ...

Here are some fun facts that you might find interesting too:

• Usage typically surges on weekends by 10%

• Daily usage peaks in the evening at bed time (local times).

• Blackberry users read the least per day as shown in our average daily number of sessions. Perhaps preoccupied by the influx of emails! Blackberry users have about 1.6 session per day, while iPhone users have 2.3 and Java phone users read the most with 2.6 sessions per day.

Steven Johnson on digital reading, and self indexing

05/11/09 10:32

With

books becoming part of this universe, "booklogs" will

prosper, with readers taking inspiring or infuriating

passages out of books and commenting on them in

public. Google will begin indexing and ranking

individual pages and paragraphs from books based on

the online chatter about them. (As the writer and

futurist Kevin Kelly says, "In the new world of

books, every bit informs another; every page reads

all the other pages.") You'll read a puzzling passage

from a novel and then instantly browse through dozens

of comments from readers around the world,

annotating, explaining or debating the passage's true

meaning.

Think of it as a permanent, global book club. As you read, you will know that at any given moment, a conversation is available about the paragraph or even sentence you are reading. Nobody will read alone anymore. Reading books will go from being a fundamentally private activity -- a direct exchange between author and reader -- to a community event, with every isolated paragraph the launching pad for a conversation with strangers around the world.

This great flowering of annotating and indexing will alter the way we discover books, too. Web publishers have long recognized that "front doors" matter much less in the Google age, as visitors come directly to individual articles through search. Increasingly, readers will stumble across books through a particularly well-linked quote on page 157, instead of an interesting cover on display at the bookstore, or a review in the local paper.

Imagine every page of every book individually competing with every page of every other book that has ever been written, each of them commented on and indexed and ranked. The unity of the book will disperse into a multitude of pages and paragraphs vying for Google's attention.

Full article here -- great thoughtful stuff!

Think of it as a permanent, global book club. As you read, you will know that at any given moment, a conversation is available about the paragraph or even sentence you are reading. Nobody will read alone anymore. Reading books will go from being a fundamentally private activity -- a direct exchange between author and reader -- to a community event, with every isolated paragraph the launching pad for a conversation with strangers around the world.

This great flowering of annotating and indexing will alter the way we discover books, too. Web publishers have long recognized that "front doors" matter much less in the Google age, as visitors come directly to individual articles through search. Increasingly, readers will stumble across books through a particularly well-linked quote on page 157, instead of an interesting cover on display at the bookstore, or a review in the local paper.

Imagine every page of every book individually competing with every page of every other book that has ever been written, each of them commented on and indexed and ranked. The unity of the book will disperse into a multitude of pages and paragraphs vying for Google's attention.

Full article here -- great thoughtful stuff!

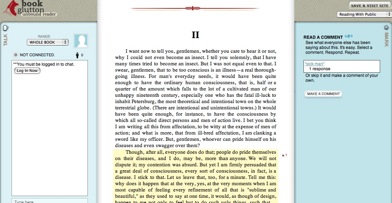

The Book Glutton's Unbound Reader

04/02/09 10:58

The

Book

Glutton is showing off its new Unbound Reader, an

online book reading site that allows you to read a

book with a group, make comments on specific passages

to share (or not) and chat while reading certain

sections of a book. An interesting concept, I'm not

sure if I would ever coordinate actually reading at

the same time as my friends, but I would love to read

other people's comments on passages.

Below is an image of the reader.

This would be a very cool experiment for a book club.

Below is an image of the reader.

This would be a very cool experiment for a book club.

A feast of book reviews

03/27/09 09:29

Indie

Book Bloggers is a collection site of a huge list

of independent book reviewers. So when you are hungry

for something to read, there's a lot of choices here

daily.

Book reviewing and ebooks

03/17/09 11:26

The

Bookish Dilettante brings the ebook cloud back

down to the ground.

Enough with the ebooks, already. I mean, I guess that ebooks are rather hot at the moment, the topic du jour, and a nice horse to pin our hopes on, but -- once I figure out what ebook format and device to go with -- how much to shell out for the ebook or whether to shell out anything at all -- how do I figure out what ebook to read? There's quite a few, and they keep on coming -- along with regular old print books.

What I mean is -- in our rush to embrace the E, let's not forget about the C - curation (i just can't let go of that word, and/or concept).

Crap as an ebook, is still just ecrap. The fact that there's infinite e-shelf space for the magnitude of possible ebook ecrap does little to help me sleep well at night.

What does help me sleep well at night -- the knowledge that there are still plenty of people (real people too, not epeople) on board who want to encourage the democratization of publishing, but at the same time, help to figure out and spread the word of what a book (e, or otherwise) is about, and have stepped up to help shepherd all kinds of books to all kinds of audiences...

The Dilettante then goes on to list her favorite sources of bookish wisdom -- go explore!

1. Readerville

2. Maud Newton

3. Flashlight Worthy

4. Books on the Nightstand

5. The Word Hoarder

6. the bat segundo show

Enough with the ebooks, already. I mean, I guess that ebooks are rather hot at the moment, the topic du jour, and a nice horse to pin our hopes on, but -- once I figure out what ebook format and device to go with -- how much to shell out for the ebook or whether to shell out anything at all -- how do I figure out what ebook to read? There's quite a few, and they keep on coming -- along with regular old print books.

What I mean is -- in our rush to embrace the E, let's not forget about the C - curation (i just can't let go of that word, and/or concept).

Crap as an ebook, is still just ecrap. The fact that there's infinite e-shelf space for the magnitude of possible ebook ecrap does little to help me sleep well at night.

What does help me sleep well at night -- the knowledge that there are still plenty of people (real people too, not epeople) on board who want to encourage the democratization of publishing, but at the same time, help to figure out and spread the word of what a book (e, or otherwise) is about, and have stepped up to help shepherd all kinds of books to all kinds of audiences...

The Dilettante then goes on to list her favorite sources of bookish wisdom -- go explore!

1. Readerville

2. Maud Newton

3. Flashlight Worthy

4. Books on the Nightstand

5. The Word Hoarder

6. the bat segundo show

People lie about reading?

03/15/09 11:24

From the

mobylives

site:

A survey carried out by the people behind World Book Day “has found that two thirds of people have claimed to have read a book they haven’t,” and, according to a story at The Bookseller by Victoria Gallagher and Katie Allen, the “most popular book to have lied about reading is 1984 by George Orwell.” The runner-up was Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, followed by James Joyce’s Ulysess. Number four was, interestingly enough, the Bible... The main reason people lied about their reading (or lack thereof) was “to impress the person they were speaking to.”

The survey also came up with some other interesting reading-related observations, such as that “people can’t bear to throw their books away, with 77% of respondents saying they buy extra bookshelves when they fill up.”

Also, a statistic that most publishers would put at somewhere closer to 90%: “11% of those asked also revealed that they have written a book but not yet had it published.”

Here's the top ten list of books people claim to have read, while not having done so:

Those who lied have claimed to have read:

1984 - George Orwell (42 percent)

War and Peace - Leo Tolstoy (31)

The Bible (24)

A Brief History of Time - Stephen Hawking (15)

Midnight's Children - Salman Rushdie (14)

In Remembrance of Things Past - Marcel Proust (9)

Dreams from My Father - Barack Obama (6)

The Selfish Gene - Richard Dawkins (6)

(Reporting by Mike Collett-White)

A survey carried out by the people behind World Book Day “has found that two thirds of people have claimed to have read a book they haven’t,” and, according to a story at The Bookseller by Victoria Gallagher and Katie Allen, the “most popular book to have lied about reading is 1984 by George Orwell.” The runner-up was Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, followed by James Joyce’s Ulysess. Number four was, interestingly enough, the Bible... The main reason people lied about their reading (or lack thereof) was “to impress the person they were speaking to.”

The survey also came up with some other interesting reading-related observations, such as that “people can’t bear to throw their books away, with 77% of respondents saying they buy extra bookshelves when they fill up.”

Also, a statistic that most publishers would put at somewhere closer to 90%: “11% of those asked also revealed that they have written a book but not yet had it published.”

Here's the top ten list of books people claim to have read, while not having done so:

Those who lied have claimed to have read:

1984 - George Orwell (42 percent)

War and Peace - Leo Tolstoy (31)

The Bible (24)

A Brief History of Time - Stephen Hawking (15)

Midnight's Children - Salman Rushdie (14)

In Remembrance of Things Past - Marcel Proust (9)

Dreams from My Father - Barack Obama (6)

The Selfish Gene - Richard Dawkins (6)

(Reporting by Mike Collett-White)

On reading, not reading, and reading for indexing

03/09/09 10:59

In response

to Pierre Bayard's

How to Talk About Books You Haven't Read,

Mandy Brown writes:

One of Bayard's arguments in How to Talk About Books is that the difference between reading and not reading is hard to pinpoint. If I only skim a book, does that count as reading or not reading? If I read a book years ago, but can no longer remember it, isn't that more akin to a state of not reading than of reading? Or, what if I have never opened a particular book, but can still speak about it authoritatively, because I know what other books it is similar to (or, put another way, I know its location in the library and what it means to be in that place) – is that a book that I have read, or a book that I have not read? Does it matter?

Someone with whom I spend a great deal of time is a significantly less avid reader than I am. Our arrangement is such that I read vigorously – making numerous recommendations about which books he should read – wherein he reads about one out of every dozen or so books I push in his direction. And yet a strange consequence of this coupling is that he can speak as authoritatively and compellingly as I can about books of which he has never so much as cracked the spine. It's as if I'm reading for two, and the act of reading expands from the initial contact (me, alone, with book in hand) to the later event (the two of us, talking about books, drinking wine). In a certain sense, he has read these books, in that he is as familiar with them (albeit through different means) as I am.

Underneath this theory of reading is an elevation of the ideas that a book espouses over the experience of reading it. The challenge I see therein is that ideas cannot be completely decoupled from the act of reading – cannot escape the material condition of the written language from which they are born. For me, especially, an idea must be judged in part on the merits of the words that describe it. The best ideas are therefore married to the most beautiful language; a divorce diminishes them both.

As indexers, we do more reading than the average soul, and yet, how much do we really absorb? I have noticed that when the material is technical, I absorb and keep nearly none of it within a month. But I do retain some - when our water purifier was behaving oddly, all the plumbing engineering indexing I have done led me to conclude it was a pressure issue, and lo and behold, it was. It didn't mean I could fix it, though! I retained the theory, but I didn't have the know-how, most likely because the engineering work I do contains formulas and applications in the broad sense, not specific valve issues under the sink.

When the material is fiction, the book itself dictates how much I retain, whether I got involved, lost myself, or got bored easily. But when the book is read with my book club, no matter what genre, I come away with a sense of owning it, it becomes a special book due to the act of sharing, and I retain all of those. The interaction and sharing of a book seems to mean I get to "keep" it.

When my indexing material is anthropological, historical, natural history, botany, biographical, or in other words very directly related to humans or nature, I retain a lot of it. Perhaps because it links into my experiences as a human, and whether I share it or not doesn't matter?

I'm wondering how the rest of you feel. How much do you retain? Is there a subject that stays with you longer?

One of Bayard's arguments in How to Talk About Books is that the difference between reading and not reading is hard to pinpoint. If I only skim a book, does that count as reading or not reading? If I read a book years ago, but can no longer remember it, isn't that more akin to a state of not reading than of reading? Or, what if I have never opened a particular book, but can still speak about it authoritatively, because I know what other books it is similar to (or, put another way, I know its location in the library and what it means to be in that place) – is that a book that I have read, or a book that I have not read? Does it matter?

Someone with whom I spend a great deal of time is a significantly less avid reader than I am. Our arrangement is such that I read vigorously – making numerous recommendations about which books he should read – wherein he reads about one out of every dozen or so books I push in his direction. And yet a strange consequence of this coupling is that he can speak as authoritatively and compellingly as I can about books of which he has never so much as cracked the spine. It's as if I'm reading for two, and the act of reading expands from the initial contact (me, alone, with book in hand) to the later event (the two of us, talking about books, drinking wine). In a certain sense, he has read these books, in that he is as familiar with them (albeit through different means) as I am.

Underneath this theory of reading is an elevation of the ideas that a book espouses over the experience of reading it. The challenge I see therein is that ideas cannot be completely decoupled from the act of reading – cannot escape the material condition of the written language from which they are born. For me, especially, an idea must be judged in part on the merits of the words that describe it. The best ideas are therefore married to the most beautiful language; a divorce diminishes them both.

As indexers, we do more reading than the average soul, and yet, how much do we really absorb? I have noticed that when the material is technical, I absorb and keep nearly none of it within a month. But I do retain some - when our water purifier was behaving oddly, all the plumbing engineering indexing I have done led me to conclude it was a pressure issue, and lo and behold, it was. It didn't mean I could fix it, though! I retained the theory, but I didn't have the know-how, most likely because the engineering work I do contains formulas and applications in the broad sense, not specific valve issues under the sink.

When the material is fiction, the book itself dictates how much I retain, whether I got involved, lost myself, or got bored easily. But when the book is read with my book club, no matter what genre, I come away with a sense of owning it, it becomes a special book due to the act of sharing, and I retain all of those. The interaction and sharing of a book seems to mean I get to "keep" it.

When my indexing material is anthropological, historical, natural history, botany, biographical, or in other words very directly related to humans or nature, I retain a lot of it. Perhaps because it links into my experiences as a human, and whether I share it or not doesn't matter?

I'm wondering how the rest of you feel. How much do you retain? Is there a subject that stays with you longer?

Like dying, everyone reads alone

03/07/09 11:12

The best

readers are obstinate. They possess a nearly

inexhaustible persistence that drives them to read,

regardless of the circumstances they find themselves

in. I’ve seen a reader absorbed in Don Quixote while

seated at a noisy bar; I’ve witnessed the

quintessential New York reader walk the streets with

a book in hand; of late I’ve seen many a reader

devour books on their iPhone (including one who

confessed to reading the entire Lord of the Rings

trilogy while scrolling with his thumb). And millions

of us read newspapers, magazines, and blogs on our

screens every day—claims that no one reads anymore

notwithstanding.

What each of these readers has in common is an ability to create solitude under circumstances that would seem to prohibit it. Reading is a necessarily solitary experience—like dying, everyone reads alone—but over the centuries readers have learned how to cultivate that solitude, how to grow it in the least hospitable environments. An experienced reader can lose herself in a good text with anything short of a war going on (and, sometimes, even then)—the horticultural equivalent of growing orchids in a desert.

Mandy Brown is a web designer who understands reading behaviors, and deliciously writes about them -- from A List Apart.

What each of these readers has in common is an ability to create solitude under circumstances that would seem to prohibit it. Reading is a necessarily solitary experience—like dying, everyone reads alone—but over the centuries readers have learned how to cultivate that solitude, how to grow it in the least hospitable environments. An experienced reader can lose herself in a good text with anything short of a war going on (and, sometimes, even then)—the horticultural equivalent of growing orchids in a desert.

Mandy Brown is a web designer who understands reading behaviors, and deliciously writes about them -- from A List Apart.

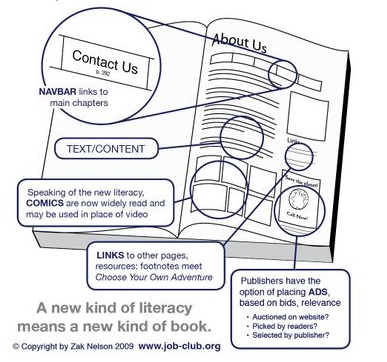

New literacy - new book styles - what about the index?

02/25/09 07:59

On WebInkNow, David Meerman Scott and Zak Nelson talk about making books more like web pages. I can see some cases where this model might work, but when I read Information Anxiety by R. S. Wurman, the design of that book, much like Nelson's idea shown above, drove me into a state of information anxiety. I must be rather linear. This much material on a page would interrupt the flow of long reading. It could have its place in guidebooks, and short content with many field-like features. Where could the index play a role? As a generator of cross references and related materials, perhaps.

Reading avoidance?

01/22/09 15:41

Are people

reading less deeply and just skimming? Loren

Dempsey suggests a new problem with information

gathering, perhaps influenced by soundbites,

snippets, twitter, and other short-but-sweet ways of

information input, resulting in people just glossing

over material and looking for highlights:

"Other content clues" - could be indexing, and could be a selling point.

The network style of consumption -- particularly mobile consumption -- calls forward services which atomize content, providing snippets, thumbnails, ringtones, abstracts, tags, ratings and feeds. All of these create a variety of hooks and hints for people for whom attention is scarce. It has even been recently suggested that this pattern of consumption is rewiring our cognitive capacities (Carr, 2008). Regardless of the longer term implications, it is clear that people need better clues about where to spend their attention in this environment, and that this is one incentive for the popularity of social approaches. This attention scarcity is apparent also in the academic environment where a bouncing and skimming style of consumption has been observed (Nicholas, et al., 2006). Palmer, et al. (2007) talk about actual 'reading avoidance'. Researchers may survey more material, but spend less time with each item, relying on abstracts and other content clues to avoid reading in full.

"Other content clues" - could be indexing, and could be a selling point.

The future of reading

12/03/08 16:16

Ursula

LeGuin's thinking on reading and publishing :

Staying Awake: Notes on the Alleged Decline in

Reading.